Popular Basque Ceramics

Popular Basque Pottery includes a large number of articles used for different purposes. What were once functional items are now in great demand by collectors for their ethnographic, cultural and decorative value.

Popular Basque Pottery includes a large number of articles used for different purposes. What were once functional items are now in great demand by collectors for their ethnographic, cultural and decorative value.

Pottery production in the Basque Country was predominantly simple and staid. More complicated and decorative articles were used for religious purposes and in stately homes.

History

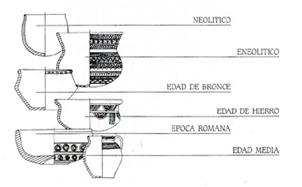

The use of pottery utensils goes back as far as the first human settlements. The development of farming and the use of tame animals gave rise to the urban settlements where the first technical breakthroughs were recorded, one of which was pottery. This occurred in the near east 7,000 years BC and arrived in the Basque Country towards the end of the 4 th millennium BC.

The use of pottery utensils goes back as far as the first human settlements. The development of farming and the use of tame animals gave rise to the urban settlements where the first technical breakthroughs were recorded, one of which was pottery. This occurred in the near east 7,000 years BC and arrived in the Basque Country towards the end of the 4 th millennium BC.

The potter’s wheel

The potter’s wheel was a major development. It could be considered the first machine invented by man. It enabled potters both to increase their production and to make more perfect items. The pottery guild started to supply a growing market.

The artefact was used in the near east 4,000 years BC. It must have been brought to the Iberian peninsula by the Phoenicians and Greeks, but it was the Romans who spread its use to the north and east of the region.

The Kiln

Pottery firing evolved towards the vertical, dual chamber, up-draught kiln used throughout Europe. Basque Country kilns were square, vertical and open at the top.

The gorse and pine branches used as fuel were burned in the lower chamber, or foguera. The pottery was placed in the upper chamber on several layers separated by pottery trays or tacas, with holes communicating the two chambers.

Once the kiln was full, the top was covered with roof tiles and bricks leaving spaces for the smoke to be released and keeping the inside hot, reaching temperatures of up to 950ºC.

Enamels

When pottery became waterproof this was a major breakthrough. Man had been attempting to make clay less porous since ancient times. We know that glassing was carried out in Persia and Asia Minor as early as 3,000 years BC but it was brought to Spain by the Arabs and became of widespread use in the 10 th and 11 th centuries. White tin enamel has been used in the Basque Country since the 17 th century.

After the Spanish Civil War, and in view of the shortage of tin from England, Basque potters started to use a different whitening technique. Once the pieces were dry, they were bathed in a white clay paste to disguise the red colour of the clay and then glassed. This method was used up to the 60’s and 70’s when the few remaining traditional potters started to close down.

Decoration

Basque pottery is fundamentally staid, and largely utilitarian and functional. It reached its decorative heights in the 17 th, 18 th and 19 th centuries, with green and manganese brown being used over tin white in most pottery from Álava, Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya. Blue over white is found in pottery from Hijona, Erenchun, Eguileta and Vitoria in Álava and from Marañón in Navarre. Green and blue motifs are also very common.

The use of these colours probably came from north of the Ebro river, from Aragon and possible eastern Spain. Since the beginning of the 20 th century, however Basque pottery was largely plain, except for items created for religious purposes.

We know that there were over 50 pottery centres in the Basque Country in the 19 th and 20 th centuries, with considerable production. However, they started to disappear nearly completely with the industrial revolution and the discovery and widespread use of new materials.

Potters and potteries

The information we have refers to the last 250-300 years, but is probably applicable to very ancient procedures. To better understand the development of pottery in the Basque Country, we need to refer to the livestock economy that was for centuries the main source of wealth for most of the Basque population. Mountainous areas were used for sheep grazing, and it is well known that in this type of economy, with herds travelling from winter to summer pastures and back, wooden utensils were always considered to be more suitable than fragile pottery. This is why pottery developed more slowly in the humid areas of the Basque Country than in the farmlands of Navarre and Álava.